Deuteronomy 27:171599 Geneva Bible

17 Cursed be he that removeth his neighbor’s [a]mark: And all the people shall say: So be it.Read full chapter

17 Cursed be he that removeth his neighbor’s [a]mark: And all the people shall say: So be it.Read full chapter

14 ¶ Thou shalt not remove thy neighbor’s mark, which they of old time have set in thine inheritance, that thou shalt inherit in the land, which the Lord thy God giveth thee to possess it.

14th Amendment never lawfully ratified. Passed statutorily.

1828 -2022 AD

Made statuatory law

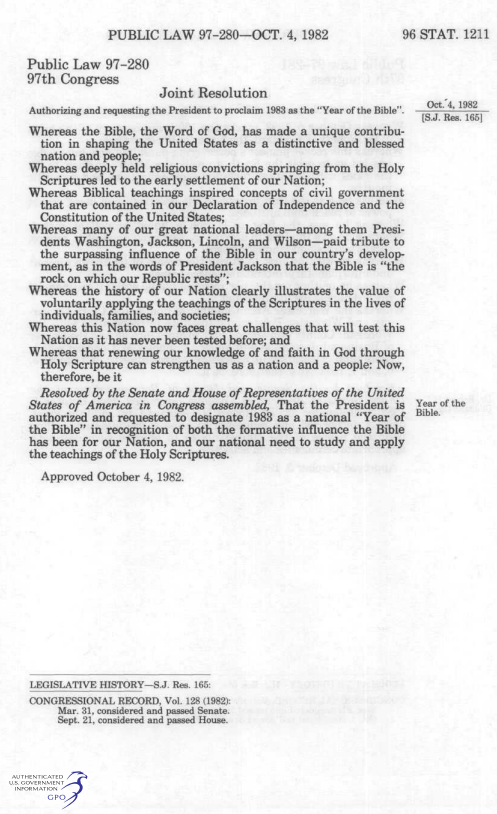

us statues at large 96 stat 1211

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-96/pdf/STATUTE-96-Pg1211.pdf

https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/STATUTE-96/STATUTE-96-Pg1211

Public Law 97-280

October 4, 1982

Joint resolution authorizing and requesting the President to proclaim 1983 as the “Year of the Bible”

S.J. Res.165

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to navigationJump to search

In February 1982, Senator William L. Armstrong and Congressman Carlos Moorhead sponsored Senate Joint Resolution 165, 96 Stat. 1211 (H.J.Res.487 in the house[1],) a joint resolution authorizing and requesting the President to proclaim 1983 as the “Year of the Bible”.[2] In the United States, 1983 was designated as the national Year of the Bible by President Ronald Reagan by Proclamation 5018,[3] made on February 3, 1983, at the annual National Prayer Breakfast. President Reagan was authorized and requested to so designate 1983 by Public Law 97-280 (Senate Joint Resolution 165], 96 Stat. 1211) passed by Congress and approved on October 4, 1982.

The law recited that the Bible “has made a unique contribution in shaping the United States as a distinctive and blessed nation and people” and that, quoting President Andrew Jackson, the Bible is “the rock on which our Republic rests”. It also acknowledged a “national need to study and apply the teachings of the Holy Scriptures.” “Can we resolve to reach, learn and try to heed the greatest message ever written, God’s Word, and the Holy Bible?” Reagan asked. “Inside its pages lie all the answers to all the problems that man has ever known.”

Paul Broun of Georgia sought a comparable declaration for 2010, but his proposal, 111 H. Con. Res. 112, did not emerge from the committee to which it was referred.[4][5]

On January 30, 2012, Pennsylvania state lawmakers declared 2012 to be the “Year of the Bible”.[6] The Resolution passed by the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, HR 535, has faced resistance from atheist groups.[7] In response, an atheist group, American Atheists, paid for the placement of a billboard in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania that protests the bill.[8]

Governor Matt Bevin of Kentucky declared both 2016 and 2017 the Year of the Bible in the state.[9][10]

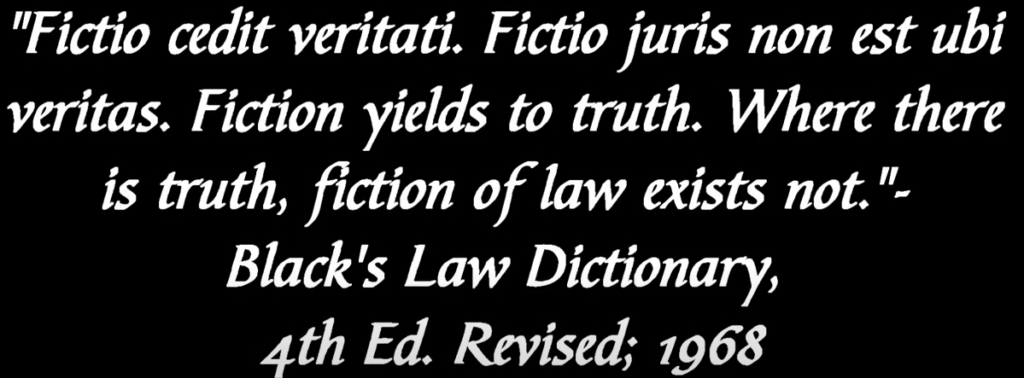

Evidence that leaves no doubt as to a particular conclusion. Examples might include a fingerprint showing that someone was present in a room, or a blood test proving who parented a child.

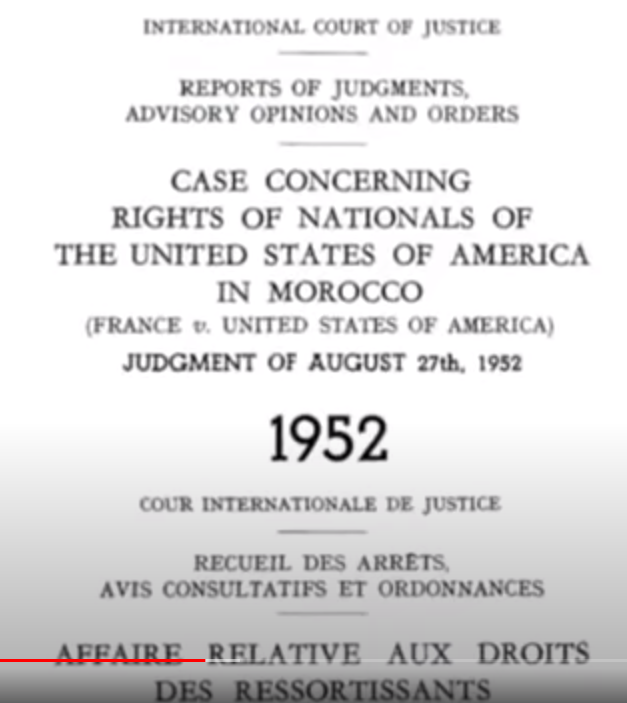

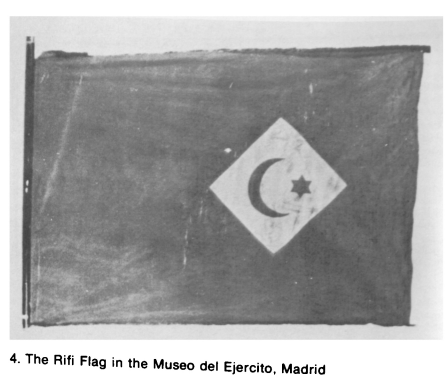

A country with a government and a flag: the Rif War in Morocco 1921-1926

Moulay Yusef ben Hassan (Arabic: مولاي يوسف بن الحسن), born in Meknes on 1882 and died in Fes on 1927, was the Alaouite sultan of Morocco from 1912 to 1927. He was the son of Hassan ben Mohammed.

The Coinage Act of 1792 (also known as the Mint Act; officially: An act establishing a mint, and regulating the Coins of the United States), passed by the United States Congress on April 2, 1792, created the United States dollar as the country’s standard unit of money, established the United States Mint, and regulated the coinage of the United States.[1] This act established the silver dollar as the unit of money in the United States, declared it to be lawful tender, and created a decimal system for U.S. currency.[2]

By the Act, the Mint was to be situated at the seat of government of the United States. The five original officers of the U.S. Mint were a Director, an Assayer, a Chief Coiner, an Engraver, and a Treasurer (not the same as the Secretary of the Treasury). The Act allowed that one person could perform the functions of Chief Coiner and Engraver. The Assayer, Chief Coiner and Treasurer were required to post a $10,000 bond with the Secretary of the Treasury.

The Act pegged the newly created United States dollar to the value of the widely used Spanish silver dollar, saying it was to have “the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current”.[3]